Saint Gregory of Sinai was born around 1265, and reposed on November 27/December 10, 1346. He was thus an older contemporary of Saint Gregory Palamas, who was born in 1296 and reposed in 1359. This year the monastery celebrated its altar feast with the help of visiting Protopsaltis John Presson from the Portland Cathedral, whose mastery of Byzantine chant enriched the community's offering of prayer and worship on this high feast. We were moved by and grateful for the presence of quite a number of pilgrims this year whose presence multiplied our joy.

The writings of Saint Gregory of Sinai have not received the intense academic interest enjoyed by his younger monastic contemporary, Saint Gregory Palamas, but his basic writings are available in volume 4 of Faber's Philokalia (212-286) with a brief introductory note (207-211). Kallistos Ware (titular Metropolitan of Diokleia, Ecumenical Patriarchate) wrote a short essay The Jesus Prayer is St Gregory of Sinai, and another British academic, David Balfour, presented Saint Gregory's Discourse on the Transfiguration in an edited version with English translation, in successive issues of Theologia, printed as a single book by Borgo Press in 1989. A recent (2004) book in modern Greek by Aggeliki Delikari studies the slavonic translation of Saint Gregory's works (Agios Grigorios o Sinaitis: I Drasi kai i Symvoli Tou sti Diadosi tou Isichasmou sta Valkania). Among the questions that interest modern academics is whether or not the two great hesychasts, Gregory of Sinai and Gregory Palamas, were in contact with one another.

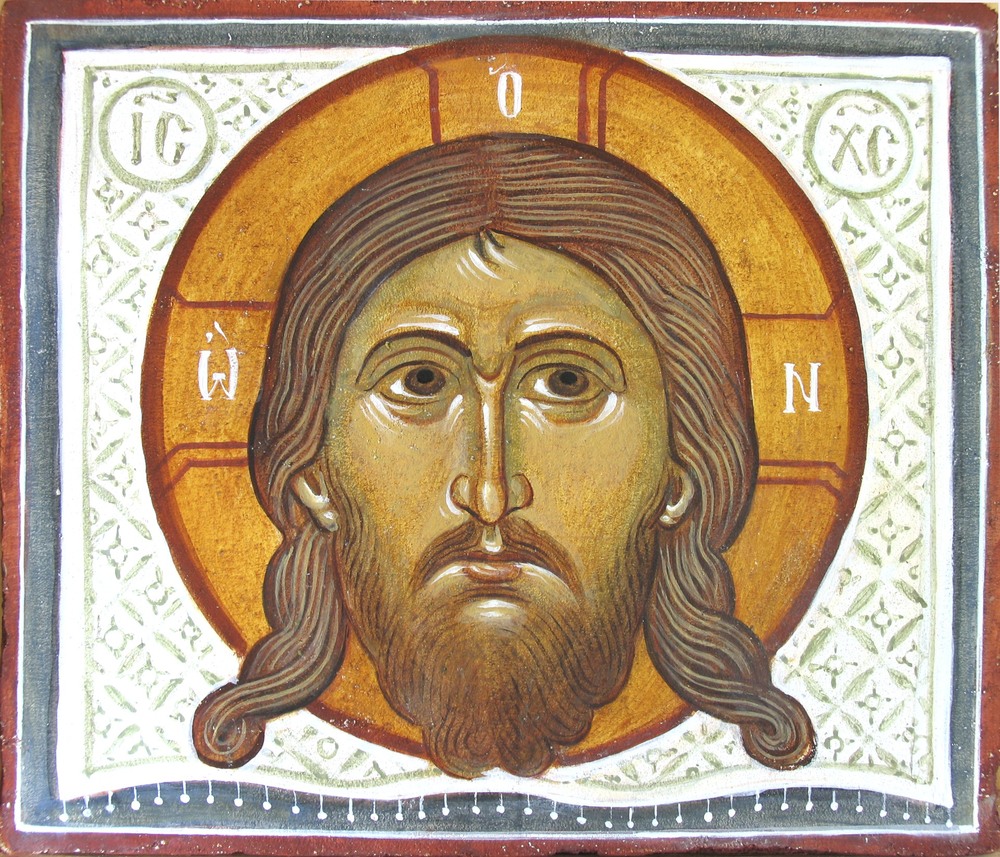

All those who feel jarred and distracted by the confusions of the 21st century will be consoled by the life of Saint Gregory of Sinai. Born and raised in early youth near Klazomenai, in Asia Minor, he was captured by marauding Moslem pirates with his family and other Greek townsmen and held for ransom. While in detention he was noted for his ability as a chanter by the Christian worshippers living under Moslem rule. Once ransomed he seems to have left his family - although still young - and to have gone to Cyprus, where he became a rassoforos monk (the first grade of monastic profession) and then moved on to Sinai where he was tonsured as a fully-professed monk (hence his title, of Sinai, although he spent comparatively little time in Sinai). There is today a small kelli (one-room monastic cabin) at some distance from the great monastery of Saint Katherine dedicated to Saint Gregory, and the contemporary local view is that he moved to this small hermitage and spent some time there. Whatever the case, for those who love the Saint it is a very moving experience indeed to stand in the wonderful katholikon of Saint Katherine's on Sinai and consider that he stood in the same building seeing the same great ikonographic program that impresses itself on worshippers today, centering on the great mosaic of the Saviour's Transfiguration filling the eastern apse of the temple.

He moved on to Crete where a monk Arsenios taught him (evidently for the first time) about the guarding of the nous, true watchfulness and pure prayer as his biographer and disciple, the Holy Patriarch Kallistos I of Constantinople wrote in his biography of his beloved Elder.

From Crete Saint Gregory moved on to Mount Athos, probably around 1300, when he would have been about 35. He did not enroll in one of the great ruling monasteries, but in a remote skete, named Magoula, the ruins of which can still be seen about a half-hour's walk eastward from the modern ruling monastery, Philotheou. Not much is left of Magoula, but again the ruins bear powerfully upon any who are devoted to Saint Gregory.

Saint Gregory was to live for about a quarter of a century in this place until, around 1325-1328 Moslem piratic incursions became so intrusive and distracting that those seeking solitude and its peace and silence opted to move away from the Holy Mountain (rather than into one of the strongly-fortified ruling monasteries). He attempted a return at some point in the 1330's but soon abandoned the idea of living on Athos altogether.

Saint Gregory ended his life beyond the borders of the Empire of the New Rome, in a place called Paroria in the Strandzha Mountains overlooking the Black Sea, safely within the borders of the Bulgarian Empire whose Emperor, John Alexander, was devoted to monasticism and its practitioners. Emperor John Alexander provided not only a monastic facility, but dedicated a number of villages to Saint Gregory's community - the basis of monastic economic life in that era - and provided, in addition, a military guard sufficient to ward off Moslem intrusions. One must note that Moslems were not Saint Gregory's only problem: monks in the Strandzha Mountains were moved to jealousy by the imperial patronage given to Saint Gregory's monastery, as also by the high esteem in which the Saint was held by numbers of Christians from far and near, and these envious neighbours stirred up no end of hardships for Saint Gregory and his community. Time, however, was on the side of the Parorian community, and by the time of Saint Gregory's death, his community counted large numbers of Greek- and Slav-speaking monks, some of whom were to play high and prominent roles in the life of the Church both in Constantinople and in the Slavic areas of the Balkans, and who were to constitute the core of what has been called the 'hesychast international'.

Saint Gregory seems to have played no role at all in the polemics of the era, in which Saint Gregory Palamas defended the practice of hesychast prayer and spiritual life against attacks both by Barlaam of Calabria (acting as a representative of western theological principles) and by a number of Orthodox Christian theologians equally uncomfortable with the assertions of articulate hesychasts, who were emboldened by an experience that was personal and clearly overwhelming, although the Greek-speaking opponents had somewhat different presuppositions at work in their polemical opposition to hesychasm than did Barlaam (and subsequent western critics).

However absent Saint Gregory of Sinai was from the extant polemics of the age, his writings agree entirely with the theological point of view defended by Saint Gregory Palamas.

After many hours of liturgical worship, our community gathered in a very different age and on a mountainside far removed from Athos and the Strandzha range feeling powerfully encompassed by the intercessions of its heavenly patron, noting one and all that for all the contributions of academic monographs to our understanding of the hesychasts of the 14th century - its golden age - nothing compares with a few hours of liturgical Vigil and Liturgy for accessing the heart of the matter. And to that, Amen.

+Sergios of Loch Lomond, Igoumenos

November 27/December 10, 2007